Discussing the beginnings of the walkman probably requires a brief look at the audio scene in the ’70s. The audio industry was enjoying success in the growing home stereo market, and the implementation of the transistor for a portable AM band receiver created a pocket radio “boom” in the ’60s which continued well into the ’70s. “Boomboxes” or battery-powered one-piece stereo systems were growing in popularity near the turn of the decade, with sound eminating through two or more loudspeakers. Consumers appreciated the ability to listen to high fidelity sound without being confined to sitting near a home stereo system. Pocket-sized micro and mini-cassette players were also successfully sold by companies like Panasonic, Toshiba and Olympus.

So, was the development of a “personal” stereo system an obvious step in the evolution of audio? Shu Ueyama of Sony cites that this invention was purely accidental. Organizational changes were taking place at Sony in 1979 and the tape recorder division was pressed to market something soon, or risk consolidation. They came up with a small cassette player capable of stereo playback. The invention was born from a tweaked Pressman (Sony’s monaural portable cassette recorder) and a pair of headphones.

Sony chairman and founder Akio Morita heard of the invention and was eager to market it. The final design of the TPS-L2, the personal stereo cassette player was completed on March 24, 1979. Sony then formulated a unique marketing campaign to sell the contraption. But first, what to call it?

The name needed to present the idea of portability, so they considered Stereo Walky. Unfortunately, Toshiba was already using the “Walky” name for their portable radio line. The new product was a descendant of the Pressman so Walkman was proposed next. Senior staff responded to this name with doubts, as it sounded like a Japanse phrase clumsily made English. The name would fly in Japan but the product would be marketed in the US as the Sound-About and in the UK as the Stowaway.

The name needed to present the idea of portability, so they considered Stereo Walky. Unfortunately, Toshiba was already using the “Walky” name for their portable radio line. The new product was a descendant of the Pressman so Walkman was proposed next. Senior staff responded to this name with doubts, as it sounded like a Japanse phrase clumsily made English. The name would fly in Japan but the product would be marketed in the US as the Sound-About and in the UK as the Stowaway.

Again, senior staff thought twice about the naming conventions–globally marketing a product with regional labels would prove costly, so Walkman was ambivalently accepted as the name of this new personal stereo system.

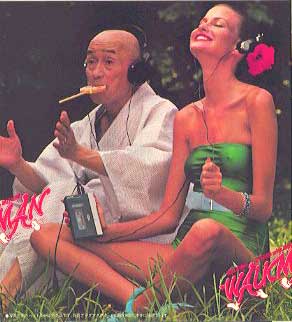

The next task was marketing the product. The story behind Sony’s market research was legendary: they didn’t do it! Said Akio Morita in a 1982 Playboy interview, “The market research is all in my head! You see, we create markets.” But how does one convince the public they need a product that they’ve never owned or seen? The first step was to get the word out to people who had influence on the public, like celebrities and people in the music industry. Sony sent Walkmans to Japanese recording artists, tv and movie stars free of charge. They also began an innovative marketing campaign, targeting younger people and active folks. The Walkman was engineered carefully to make it affordable to this market, priced to be around 33,000 yen (Sony was 33 years old at the time. Coincidence?) The imagery Sony successfully used around their Walkman gave the feelings of fun, youth and most importantly, freedom. Their invention allowed one to bring an exceptional listening experience anywhere.

The next task was marketing the product. The story behind Sony’s market research was legendary: they didn’t do it! Said Akio Morita in a 1982 Playboy interview, “The market research is all in my head! You see, we create markets.” But how does one convince the public they need a product that they’ve never owned or seen? The first step was to get the word out to people who had influence on the public, like celebrities and people in the music industry. Sony sent Walkmans to Japanese recording artists, tv and movie stars free of charge. They also began an innovative marketing campaign, targeting younger people and active folks. The Walkman was engineered carefully to make it affordable to this market, priced to be around 33,000 yen (Sony was 33 years old at the time. Coincidence?) The imagery Sony successfully used around their Walkman gave the feelings of fun, youth and most importantly, freedom. Their invention allowed one to bring an exceptional listening experience anywhere.

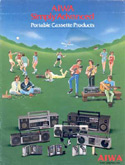

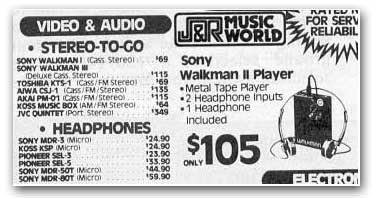

The Walkman craze began in Japan and reached the US by 1980. Other audio companies jumped on the personal stereo bandwagon, and by Spring of 1981, at least two dozen companies were selling similar devices, many of which were marketed with catchy names of their own. Toshiba had their Stereo Walky, Infinity had their Intimate, Panasonic sold their Stereo-To-Go, GE marketed their Escape, and even discount audio producer Craig followed suit with the Soundalong. Styles and colors varied from the Walkman, but several key features were found on early models: two headphone jacks (listen with a friend!) separate left and right channel volume controls, and a neat but impractical “hotline” switch, as Sony called it. Pushing this button turned on an ambient microphone so the listener could hear the noise around him instead of the music. Strangely enough, all of these features disappeared from portables a year or two later.

The Walkman craze began in Japan and reached the US by 1980. Other audio companies jumped on the personal stereo bandwagon, and by Spring of 1981, at least two dozen companies were selling similar devices, many of which were marketed with catchy names of their own. Toshiba had their Stereo Walky, Infinity had their Intimate, Panasonic sold their Stereo-To-Go, GE marketed their Escape, and even discount audio producer Craig followed suit with the Soundalong. Styles and colors varied from the Walkman, but several key features were found on early models: two headphone jacks (listen with a friend!) separate left and right channel volume controls, and a neat but impractical “hotline” switch, as Sony called it. Pushing this button turned on an ambient microphone so the listener could hear the noise around him instead of the music. Strangely enough, all of these features disappeared from portables a year or two later.

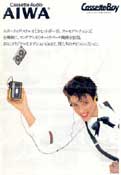

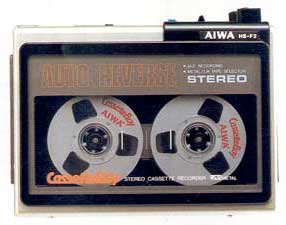

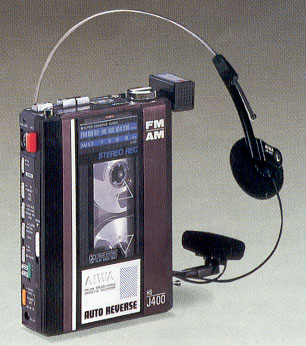

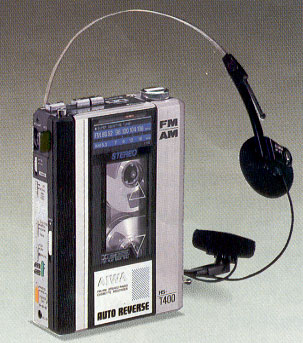

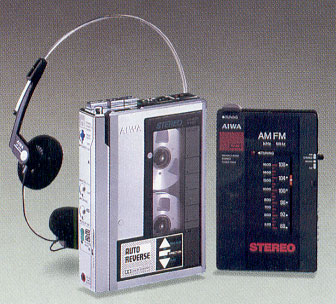

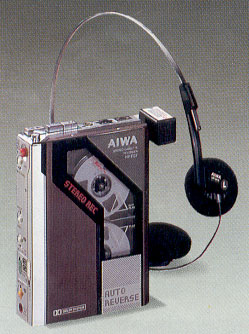

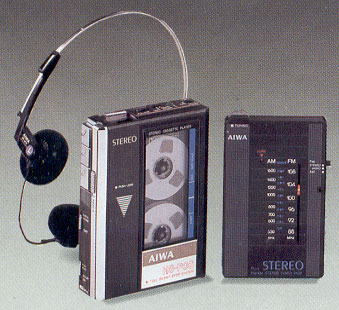

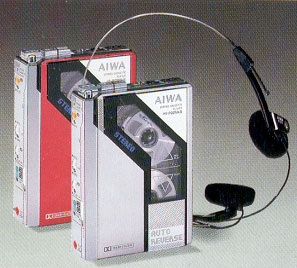

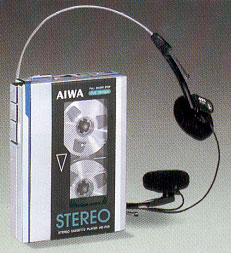

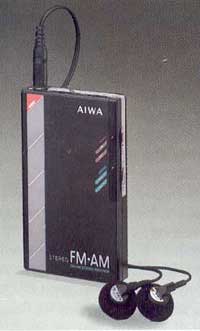

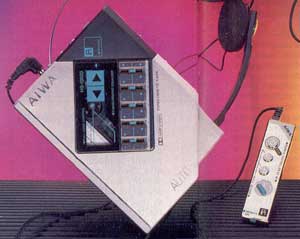

While one may be tempted to criticize these other companies as Walkman “wannabes,” We should instead appreciate their accomplishments, for together they provided us with what we refer to as the walkman “Golden Age.” A marketing person described this movement accurately. “During any product development,” he said, “the first few years are associated with innovative design and quality.” He’s absolutely right. Many personal stereo products emerged and surpassed the Walkman in terms of features and price. Sanyo’s M5550 was smaller than the Walkman, more durable with its all-metal chassis and contained a variable tape speed dial. Aiwa, owned by Sony since 1969 created a product line initialized by their TPS30, a personal stereo cassette recorder. Akai’s PM-01 had FM tuning capability through the aid of a cassette-shaped radio module. What an incredible concept: in an effort to confine the space of a personal stereo, how can one add features at the same time? The logical, yet nonetheless remarkable idea was to place a radio within an audio cassette chassis and engineer it to send the audio into its cassette player home. Toshiba had the same functionality and offered an AM module, also.

While one may be tempted to criticize these other companies as Walkman “wannabes,” We should instead appreciate their accomplishments, for together they provided us with what we refer to as the walkman “Golden Age.” A marketing person described this movement accurately. “During any product development,” he said, “the first few years are associated with innovative design and quality.” He’s absolutely right. Many personal stereo products emerged and surpassed the Walkman in terms of features and price. Sanyo’s M5550 was smaller than the Walkman, more durable with its all-metal chassis and contained a variable tape speed dial. Aiwa, owned by Sony since 1969 created a product line initialized by their TPS30, a personal stereo cassette recorder. Akai’s PM-01 had FM tuning capability through the aid of a cassette-shaped radio module. What an incredible concept: in an effort to confine the space of a personal stereo, how can one add features at the same time? The logical, yet nonetheless remarkable idea was to place a radio within an audio cassette chassis and engineer it to send the audio into its cassette player home. Toshiba had the same functionality and offered an AM module, also.

Companies like Infinity worked at sound quality. Their Intimate offered Dolby noise reduction. Koss sold their radio-only Music Box with a set of their well-reputed over-the-ear headphones, and offered circuitry to notify the user when he or she was listening to audio that was “too loud.” High grade stereo component manufacturer Proton even stepped into the ring and sold a model that included some hi-tech circuitry previously available only on $1000+ stereo equipment.

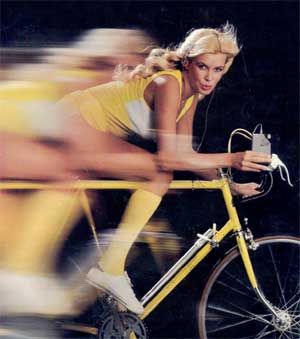

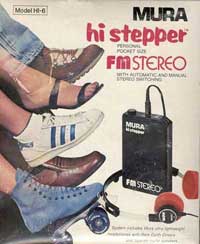

Many groaned after seeing the $150 price tags of Sony and Toshiba and settled for their $20 earphone-clad radios until names like Unic, Randix Audiologic, Craig and Yorx came along cheap personal stereos. Discount manufacturers seized the opportunity during the portable stereo craze. Products similar in shape and functionality (but not necessarily quality) were marketed as the Walkman, using photographs of people on the go, in sneakers, roller skates and on bicycles. Fortunately, these companies made a personal stereo available for everyone.

Many groaned after seeing the $150 price tags of Sony and Toshiba and settled for their $20 earphone-clad radios until names like Unic, Randix Audiologic, Craig and Yorx came along cheap personal stereos. Discount manufacturers seized the opportunity during the portable stereo craze. Products similar in shape and functionality (but not necessarily quality) were marketed as the Walkman, using photographs of people on the go, in sneakers, roller skates and on bicycles. Fortunately, these companies made a personal stereo available for everyone.

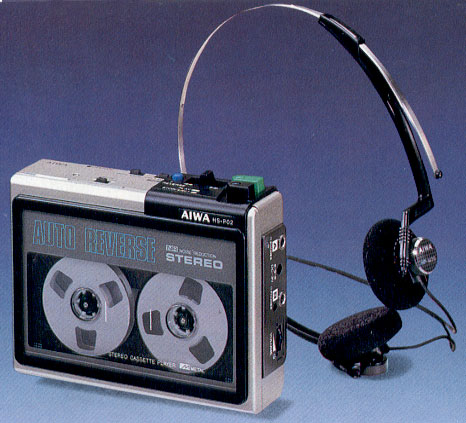

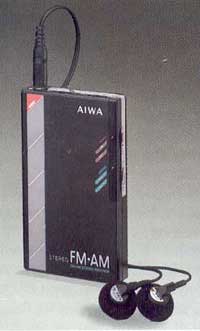

Competition was strong as throughout the early ’80s and new ideas were popping all of time: Sony feeling the pressure worked on engineering their Walkman line be smaller, while still looking and sounding better. Long Island, New York audio company Mura decided to focus on the radio-only stereo, so they enhanced functionality in their Hi Stepper line. One model even offered TV audio reception. Popular US electronics distributors like Radio Shack, Sears and JC Penney also jumped on the bandwagon by selling their own personal stereos. Overseas audio manufacturers like Grundig and ITT were selling similar portables that rivaled the quality of Japanese brands. JVC announced the “be-all” of portables in 1982: the CQ-F22K. This was the first portable stereo that included all of the features we’re accustomed to having today, like Dolby noise reduction, auto-reverse and AM/FM tuning. Perhaps the most exotic feature offered on a personal stereo at the time was the wireless feature discovered on some gray market Aiwa CS-J1 units. They apparently transmitted an audio signal that would be received by special headphones. Sony offered their affordable Walkman II, or WM-2 in a small, shapely all-metal chassis. This remains the most successful model of all time, selling 2 1/2 million units. By 1983, Everyone was shopping for a personal stereo.

Competition was strong as throughout the early ’80s and new ideas were popping all of time: Sony feeling the pressure worked on engineering their Walkman line be smaller, while still looking and sounding better. Long Island, New York audio company Mura decided to focus on the radio-only stereo, so they enhanced functionality in their Hi Stepper line. One model even offered TV audio reception. Popular US electronics distributors like Radio Shack, Sears and JC Penney also jumped on the bandwagon by selling their own personal stereos. Overseas audio manufacturers like Grundig and ITT were selling similar portables that rivaled the quality of Japanese brands. JVC announced the “be-all” of portables in 1982: the CQ-F22K. This was the first portable stereo that included all of the features we’re accustomed to having today, like Dolby noise reduction, auto-reverse and AM/FM tuning. Perhaps the most exotic feature offered on a personal stereo at the time was the wireless feature discovered on some gray market Aiwa CS-J1 units. They apparently transmitted an audio signal that would be received by special headphones. Sony offered their affordable Walkman II, or WM-2 in a small, shapely all-metal chassis. This remains the most successful model of all time, selling 2 1/2 million units. By 1983, Everyone was shopping for a personal stereo.

As with any fad, many groups raised concerns with the Walkman. Were we at risk while performing daily activities like driving or walking around town oblivious to the world around us? Would we go deaf or catch brain damage? Would we turn into anti-social creatures, encapsulated in our little personal stereo world? Of course, these concerns didn’t slow the Walkman movement even slightly.

We caught MTV’s tongue-in-cheek airing of “Video Killed the Radio Star,” but teenagers didn’t think twice about strapping on a pair of samarium cobalt headphones and banging their heads to Autograph’s “Turn Up The Radio.” The generation gap widened as young people became “wired.” With the exception of school, many kids spent their waking days with a personal stereo on the hip.

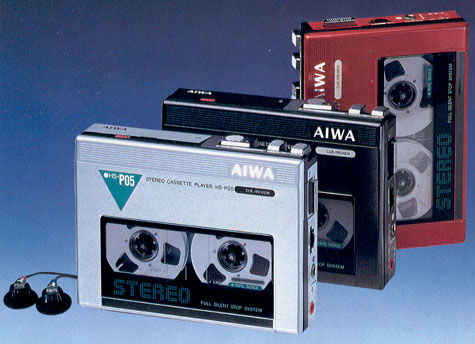

Several initial players in the personal stereo market dropped out as the ’80s endured, but Sony, Aiwa, Toshiba, Sharp, Panasonic and Sanyo thrived. Product lines widened from $25 “disposables” to $200 professional-grade models. Niche models popped up, like Sony’s durable Sports line, and Aiwa’s featured-packed J Series recorders with stereo microphones and wired remote controls. Perhaps Sanyo and Sharp enjoyed the most success with their inexpensive portables, aimed at young and price-conscious buyers. If you were sick of wasting AA batteries, you had solar-powered walkmans available, like Sony’s WM-F107 and Mura’s Sun Stepper. Sony and Panasonic even offered models that contained two cassette drives, so you can listen to one cassette right after another, or dub a copy of an original recording.

We also noticed the blossoming of an industry to provide aftermarket accessories for personal stereos. We’ve all had to buy a second set of headphones at some point, some of us purchased little desktop speakers allowing our little personal stereo to become a home one of sorts. Unitech marketed a cushioned vinyl travel bag for your walkman that contained little stereo speakers inside. Simply pop your unit into it and you’ve got a boombox. Signatech sold a trendy vest that sported loudspeakers on the shoulders and special walkman “pocket” for an audio source.

We also noticed the blossoming of an industry to provide aftermarket accessories for personal stereos. We’ve all had to buy a second set of headphones at some point, some of us purchased little desktop speakers allowing our little personal stereo to become a home one of sorts. Unitech marketed a cushioned vinyl travel bag for your walkman that contained little stereo speakers inside. Simply pop your unit into it and you’ve got a boombox. Signatech sold a trendy vest that sported loudspeakers on the shoulders and special walkman “pocket” for an audio source.

The walkman craze (note the lower-case “w”, as the name was entered into the Oxford English Dictionary in 1986) continued its run, and prices dipped as functionality rose. By 1985 many models featured graphic equalizers for even better sound, tape direction change and auto-reverse features for ease of use. The average model required two batteries, as opposed to the typical four in 1980. Sony announced a belt-free “direct drive” mechanism for remarkably low wow and flutter (terms that describe the warbling noise in audio cassette playback). Panasonic offered their “Radio Card,” the thinnest pesonal stereo radio ever.

1986 marks the year that we identify the beginning of the end for the walkman, for it was in this year that Sony announced the D-50, a portable audio device that played a new digital medium called the compact disc. The public was eager to hear the “perfect” sound of the CD so they rushed out to grab a “Discman.” Audio companies again followed Sony and began focusing their efforts to this new technology. Walkmans didn’t wane in popularity initially, for all pre-recorded music was available in cassette form and there was no consumer CD recorder at the time. As we approached the turn of the decade, features digital tuning, clocks, alarms, rechargeable batteries, wireless headphones and logic controls. But the walkman novelty had worn off, replaced by the CD and later the mini-disc.

1986 marks the year that we identify the beginning of the end for the walkman, for it was in this year that Sony announced the D-50, a portable audio device that played a new digital medium called the compact disc. The public was eager to hear the “perfect” sound of the CD so they rushed out to grab a “Discman.” Audio companies again followed Sony and began focusing their efforts to this new technology. Walkmans didn’t wane in popularity initially, for all pre-recorded music was available in cassette form and there was no consumer CD recorder at the time. As we approached the turn of the decade, features digital tuning, clocks, alarms, rechargeable batteries, wireless headphones and logic controls. But the walkman novelty had worn off, replaced by the CD and later the mini-disc.

Today, personal stereo cassette players and radios bear little resemblance to their predecessors from years prior. They’re absolutely disposable, averaging $20 in price and offering key features like pastel and chromey colors, rounded edges and clear plastic chassis. Obviously little effort is put into the design or engineering of the walkman, for manufacturers believe the audio cassette is a dying medium, soon to be replaced with the digital technology of hard disks and RAM cards.

This sad state is what drove us to build this site. We hope you can appreciate the obsolete device we call the walkman. It changed our perception of sound and became a cultural icon. It was a gadget with soul.